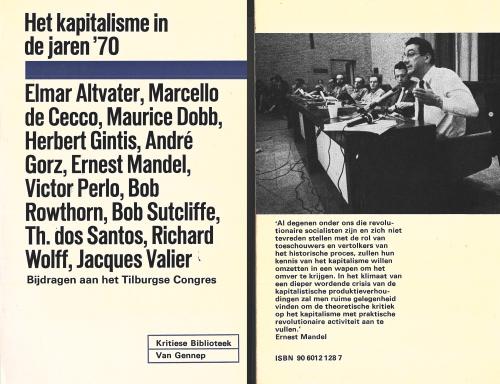

This lecture was Mandel’s contribution to the 1970 congress ‘Capitalism in the Seventies’, organized by faculty and students of the Hogeschool Tilburg, the Netherlands.

I

The relationship between theory and history presents one of the most challenging problems of the Marxist method. The relationship between the general laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production laid bare by Marx in Das Kapital and the history of that mode of production is a key aspect of this problem.

The fact that this relationship has not yet been definitely clarified is a measure of the difficulties of the problem. It has become commonplace to state that the laws of motion of capitalism, discovered by Marx, result from a dialectical analysis conducted on a high level of abstraction. As Marx pointed out himself, however, a tremendous labour of assimilation, of empirical data (both of socio-economic history and of social and economic theory, or ideology) preceded these discoveries. On the other hand, a scientifically satisfactory analysis of ‘concrete’ capitalism – i.e. of a specific socio-economic formation in a specific country in a specific epoch – has to start from the ‘laws’ discovered by Marx, if it has to avoid getting swallowed up in irrelevant or insignificant detail, thereby becoming unable to foresee or even understand predominant trends of development. But to refuse to check and re-check the laws of motion against empirical data and historical evidence implies the risk of transforming them from tools of understanding long-term developments into dogmas, divorced from reality.

The Marxist method, as often specified by Marx and Lenin themselves, has to avoid these dual pitfalls of empiricism and dogmatism. The integration of theory and history is key to its correct application. A reintegration of the laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production and contemporary socio-economic history is therefore a task of utmost importance for Marxist economists.

The necessity of such a reintegration has sometimes been denied with reference to the specific character of ‘laws of motion’ to a mode of production – and certainly those of capitalism. It has been alleged that these ‘laws’ are, after all, only of the nature of ‘tendencies’, and not strict mechanical causal links like those prevailing in 19th-century natural science. Each of these tendencies, furthermore, is supposed to produce counter-tendencies which partially offset and neutralize them. Marx’s handling, in chapters 13, 14 and 15 of volume III of Capital, of the tendency of the average rate of profit to decline is often cited as a classical example of such a combination of tendency and counter-tendency. And from there the conclusion is drawn that it is hardly possible, even hardly necessary, to find empirical-historical ‘evidence’ for these ‘laws of motion’. Sometimes it has even been alleged that this speaker’s attempt to look for such evidence implies a basic misunderstanding of Marx’s purpose and methods, the two levels of abstraction, that of the ‘pure’ mode of production and that of the ‘concrete’ historical process, being so far removed from each other that they can hardly ever meet.

In in any case, it is not difficult to prove that Marx rejected this quasi-total divorce of theoretical analysis from empirical evidence in the most categorical way. What this divorce implies in reality is a significant retreat from materialist dialectics. Once laws of motion are considered so abstract that their concrete manifestation in history cannot be discovered, or supported by empirical evidence or is even considered inexistent, then their discovery stops beings a tool to interpret historical reality, and thus becomes inadequate as a tool for changing reality. The dimension of ‘praxis’ – central to Marxist epistemology – is then eliminated from the system altogether, and this becomes a kind of speculative socio-economic philosophy of an idealist nature, in which the ‘laws of motion’ play a similar ghost-like role as Hegel’s Weltgeist, which you can never touch with your fingertips so to speak. Tendencies which never manifest themselves materially are not tendencies at all, from the point of view of historical materialism. They are a false consciousness or, if one prefers that expression in the realm of scientific endeavours, scientific errors.

It is certain, on the other hand, that, while the ‘laws of motion’ of the capitalist mode of production are indispensable to understand and to explain the history of capitalism, they are insufficient to explain this history on their alone. The capitalist mode of production did not develop in a void, but in a specific socio-economic framework which was significantly different in, say, Western Europe, North America, Japan and continental Asia. The specific socio-economic formations which arose in the 18th and 19th centuries and which are called ‘capitalist societies’ reproduce in various degrees combinations of past modes of production with successive stages of development of the new mode of production. The organic unity of world capitalism – of the capitalist mode of production as a world system – does not mean these specific combinations have only secondary importance from an analytical point of view. On the contrary, it is to a large extent precisely a function of this basic law of uneven and combined development, without which such phenomena as English laissez-faire capitalism between Waterloo and Sedan, subsequent imperialism, and therefrom resulting victorious socialist revolutions in relatively backward countries like Russia and China, cannot be fully understood.

To the operation of the law of uneven and combined development in the field of socio-economic history must be added the results of its operation regarding the interrelationship between social infrastructure and social superstructure, in other words, the uneven and combined development of the subjective factor of history as related to the objective one. Class consciousness is not a mechanical reflection of class strength. Class struggle in turn is a direct function of neither objective relationships of forces between classes, nor of class consciousness, but of specific and constantly varying combinations between both.

History has shown us relative low levels of organization and consciousness in countries where the working class has great numerical strength; relatively high levels of organization and of numerical strength combined with low level of consciousness; relatively high levels of organization and consciousness combined with little numerical strength; and many variations more.

We know, however, that the division of the net product produced by living labour – calculated on the basis of the labour theory of value – depends precisely on the intensity and results of the class struggle – and that this division of the net product is evidently one of the factors which influence the rate of accumulation, the rate of productive investment, and therefore the rate of growth of the capitalist economy.

We can therefore conclude that a reintegration of the ‘abstract’ laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production and the ‘concrete’ socio-economic history of that system must also integrate into the analysis class struggle (wage labour), the state, international trade and the world market. And what do we find here but the famous initial plan of Capital as contained in Marx’s letter to Engels of 2 April 1858!

II

Why has this reintegration of theory and history, which Marx achieved in such a masterly way for the capitalist mode of production in general, not been successfully reproduced for each successive stage of capitalism? Why do we not yet possess a satisfactory history of capitalism on the basis of the basic laws of motion of that system – with the reservations just indicated – not to speak of a satisfactory explanation of the new stage of capitalism evidently ushered in since the Second World War?

Many social and political factors can be cited for this important time-lag of consciousness as compared to material reality, the least the paralyzing apologetic grip which Stalinism – itself both object and subject of the historical process – held on Marxist theory for more than a quarter of a century, and whose ultimate effects continue to influence and vitiate theoretical analysis and production today.

But beyond these socially determined factors which have inhibited a satisfactory development of Marxist economic theory in the 20th century, there is an internal logic in this development which explains, at least in part, why so many efforts in that direction have failed. Two aspects of this logic merit particular attention. One concerns the analytical tools; the other, the analytical method. Nearly all attempts to explain specific stages of the capitalist mode of production – or specific problems arising out of these stages – by the ‘laws of motion’ of the capitalist mode of production as laid bare in Capital have started from Marx’s reproduction schemes in volume II of Capital. It is our contention that these schemes, as developed by Marx, are inadequate for that purpose and irrelevant to that problem. Therefore, any attempt to use them in order to ‘prove’ either the final ‘collapse’ of capitalism or the origins of monopoly capitalism, or the nature of ‘neo-capitalism’ or ‘late capitalism’ are doomed to failure.

The reasons for this contention were explained in a convincing way by the late Roman Rosdolsky, and they are at the root of the failure of two of the most brilliant attempts to reintegrate the history of capitalism and the laws of motion of capitalism, by Rosa Luxemburg and Henryk Grossmann. Marx’s schemes of reproduction have a specific purpose in his analysis of capitalism. Their function is to explain why a system based on ‘pure’ market anarchy, on millions of independent decisions of buying and selling taken by private commodity owners, is not in constant turmoil and disintegration, but can periodically lead to equilibrium. The famous formula for equilibrium Iv + Isv = IIc indicates that the system is in equilibrium when effective demand of sector I for commodities produced in sector II equals effective demand of sector II for commodities produced in sector I. The ‘laws of motion’ can be integrated in these reproduction schemes.

These can be rewritten in such a way that, as the mass of surplus-value increases, the organic composition of capital increases, the rate of exploitation increases, while the rate of profit declines, and so on. But the function of the reproduction schemes remains the same: to show that periodic equilibrium is possible, and what the general conditions for such equilibrium are.

It is, however, evident that capitalist growth is not balanced, that the very notion of growth under capitalism implies a break-up of equilibrium, that capitalist development, not to speak of the ‘laws of motion’ of capitalism, cannot be subsumed under the heading ‘system in equilibrium’. On the contrary, the laws of motion growing out of the inner contradictions of the system imply inevitable and unavoidable disequilibrium. And by their very nature, the reproduction schemes exemplified by volume III of Capital and applied by nearly all disciples of Marx are inadequate to study the operations of these laws of motion. They are tools to show why equilibrium is not the rule but the exception under capitalism and how uneven growth (that is what disequilibrium means in the final analyses) between the different sectors functions under capitalism. Another set of schemes has to be worked out – ‘dynamic schemes’ so to speak – to represent that uneven growth as the more general modus operandi of the capitalist system of which the equilibrium schemes of volume III of Capital would be only a special case. Uneven rates of growth induced by uneven rates of profit (partially a function of transfers of value from sector II to sector I) leading to uneven rates of accumulation and of organic composition of capital, temporarily corrected by uneven rates of crisis between the two sectors, would be the essential ‘dynamic’ elements modifying the reproduction schemes in order to transform them into tools for the study of capitalist development (a dialectical unity of disequilibrium and equilibrium).

Passing from the insufficiency of tools to the insufficiency of the analytical method, we are struck by a dominant aspect of the discussion of the problem of capitalist development (and ‘collapse’) for half a century: the attempt by each author or ‘school’ to reduce the problem to one basic factor. Realization of surplus-value for Luxemburg (i.e. the expansion of the market); decline of the rate of profit for Hilferding-Lenin; increasing need for capital accumulation for Henryk Grossman; division of surplus-value between productive accumulation and unproductive consumption for Kalcki and the theoreticians of the ‘permanent arms economy’: these are but a few examples of ‘single factor’ theories formulated to explain the emergence of imperialism or stagnation of the system. What is tacitly implied in these theories is that there is but one single independent variable in the system emerging from Marx’s ‘laws of motion’ of the capitalist mode of production. All other ‘laws’ more or less automatically fall into place, once this single variable operates in one way or another. But this assumption is contradicted by all specific remarks by Marx himself and is irreconcilable with the concept of the capitalist mode of production as a dynamic totality in which the interaction of all basic ‘laws of motion’ is necessary to assure a given specific development. This concept implies that to a certain extent – of course not in an absolute and mechanical way – all basic variables of the system are partially independent variables.

First, international migration and market expansion can become partially independent variables, completely modifying the outcome of development in this respect. Without these factors as partially independent variables it is impossible to explain why in Western Europe, during the ‘long period of relative stagnation’ between 1876 and 1895, notwithstanding a slowdown of the rate of accumulation, real wages rose rather steeply and the rate of exploitation increased much less rapidly, or even decreased a little.

Second, the increase in the organic composition of capital is likewise not just a mechanical function of technical progress (of the replacement of living labour by dead labour, i.e. the constant accumulation of ‘labour-saving’ devices, induced by capitalist competition), although it depends to a large extent upon it. The unit costs of fixed capital and the general trend of raw materials value also influence the organic composition of capital in a significant way as partially independent variables. When technological progress is stepped up, the tempo of modernization and replacement of fixed capital increases, but at the same time the relative value of raw materials declines steeply compared to that of consumer goods, while the unit cost of more and more up-to-date and perfected fixed producer goods tends to remain stable or even to decline, the outcome of the whole process might be much greater stability in the organic composition of capital than the pace of technological innovation would at first sight suggest. This is just one of the reasons why average profits in the period 1950-1966 fell less than one might think: the organic composition of capital increased less due to technological intensification than might have seemed at first glance. We therefore conclude that an attempt to explain successive stages in the history of capitalism in function of the laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production needs to bring into play all these basic laws of motion simultaneously, without unduly privileging a single one. Be it said in passing, this is a return to the method used by Marx himself, to explain the capitalist mode of production as a complex and contradictory totality.

III

There is consensus among Marxists to view the development of capitalism in a classical triad:(1) Pre-industrial monopoly capitalism trading, banking and manufacturing monopolies in the period prior to the industrial revolution.(2) Industrial laissez-faire capitalism resulting from the industrial revolution.(3) Monopoly capitalism as finance and industrial monopoly capitalism growing out of free competition capitalism. We do not want to challenge this consensus but we should like to introduce a geographical division into this triad which leads to a rather striking modification of it. In the epoch of pre-industrial capital, the predominant tendency is one of growing international concentration of money capital as opposed to growing international equalization of productivity of labour. The dispute about international levels of agricultural productivity is far from being settled, indeed it might well go on for a long time. But there is hardly any doubt that the relative levels of productivity of manufacturing labour in, say late 17th- and early 18th-century Holland, Britain, China, Japan, and parts of India, were not very different. The seeds for the future explosion of international inequality of development between nations inside the world system were being laid in the epoch of pre-industrial capitalism, as a result of a huge process of international concentration of money capital in Western Europe, taking the form of direct or indirect plunder of Asia, Latin America and Africa and partially Eastern Europe, by conquering and commercial colonialism, to which must be added the slave trade and the results of slave labour. When we pass from the period of manufacturing to that of industrial capitalism in the first place, we witness a significant change in the inter-relationship of various geographical parts of the world capitalist system. Internationally, uneven development of money capital has now transformed itself into uneven development of productive capital, i.e. of industry and productivity of labour. Whereas capitalism is building up a world market into which the broadest possible variety and combination of ‘local’ or ‘national’ modes of production is being integrated – from the slave-worked cotton plantations of the southern United States to the near-feudal landed estates of Romania and Hungary and the primitive tribal communities of certain regions of tropical Africa – it is not building up modern industry on a world scale. Modern industry remains a monopoly of a few countries (or even regions) of Western Europe (and to a certain extent North America). Laissez-faire capitalism in England and Western Europe is preconditioned by this world monopoly of capitalist industry (of high productivity of labour) in the West. In other words, a combined process of horizontal industrialization inside its own borders and of rapid expansion of foreign markets in non-industrialized countries created the necessary conditions for 19th-century expansion of ‘free competition’ capitalism in Western Europe. The first part of this process created a permanent supply of cheap labour for expanding industry through the ruthless destruction of pre-industrial peasant and handicraft enterprise. This large internal reserve army of labour made it possible to keep wages relatively low and the rate of profit and of capital accumulation relatively high. The shortcomings resulting from this combination – the relative limitations of an internal market proves the low level of wages – were more than neutralized by the rapid expansion of exports, i.e. of foreign markets.

What factors started to undermine the functioning of this system of ‘free competition’ capitalism in the West? Long before it had reached its absolute social and geographical limit, with the possible exception of Britain ‘horizontal’ industrialization in the West ran into growing economic problems. Agricultural regions inside industrialized nations played a triple role of safety valve, of props for a relatively high rate of profit, and capita accumulation. They supplied cheap food, i.e. relatively low wages, and relatively cheap materials of agricultural origin and created an abundant supply of surplus-labour. They played the role of an additional market, over and above the one consisting of workers and capitalists alone. Only Britain, which had taken the lion share of the world market for itself, could allow itself the luxury of a vanishing native agriculture. All other Western capitalist powers had to maintain these ‘inner colonies’, and not only for political reasons as is often alleged. That is why in nearly all Western countries industrialization tended to take the form of clusters around raw material sources (coal and iron), ports, or large capital cities (markets for consumer goods), complemented by large regions of a semi-industrial or non-industrial nature. ‘Free competition’ capitalism was based not only on international but also on internal regional monopolies of industry.

But the economic limitations imposed upon ‘horizontal’ industrialization implied stepped up ‘vertical’ industrialization, i.e. attempts to basically renew techniques in pre-existing industries. This led to a strong increase in the organic composition of capital, a strong increase in competition, a strong increase in centralization and concentration of capital, phenomena which have been generally and correctly interpreted as contributing to the decline of ‘free competition’, to the birth of monopoly capitalism and to the birth of imperialism.

Two additional factors have to be introduced into the analysis, in order to fully explain the shift in the modus operandi of the world capitalist system initiated around the beginning of the 1880s. Persistent misery of the Western proletariat, combined with loss of hope in a rapid change of social conditions after the defeat of the revolution of 1848, induced a massive movement of migration of European labour to North and South America and to a lesser extent Australia and North and South Africa. The immediate effects of this international migration were favourable for Western European capitalism, inasmuch as they created additional sources of cheap food which helped to keep wages low. But the long-term effects were doubly threatening. In the first place, a growing concentration of population in North America created an inner market which, after overcoming initial difficulties – especially through elimination of the slave plantation system in the South – became highly conducive to stepped-up capital accumulation and industrialization, with, from the start, a very high level of productivity of labour and of industrial technology, made necessary by initially higher wages than in Europe. This in turn led to the birth of the most formidable competitor for Western Europe, one which would overtake it after the First World War. In the second place, massive emigration of labour from Europe tended to produce a decline in the reserve army of labour. This in turn facilitated the emergence of mass trade unions and social-democratic parties, i.e. a shift in the social relationship of forces which, together with modified relations between supply and demand of labour power, induced a steady increase of real wages in the second half and especially the fourth quarter of the 19th century.

The end of the laissez-faire period was thus determined by a two-sided erosion of the rate of profit: as a result of steep increase in the organic composition of capital on one hand, and of a decline in the rate of surplus-value on the other. Increased international competition, export of capital to underdeveloped countries in order to employ cheap labour and produce cheap raw materials, thereby counteracting or neutralizing the decline in the rate of profit, permit us now to complement the earlier reasons given for the emergence of monopoly capitalism and imperialism. World integration of capitalism became stronger, but at the same time international, international unevenness of development became even more pronounced.

From the 1880s, massive export of Western capital to so-called ‘third world’ countries resulted in a massive relative decline in raw material prices as compared with prices of finished manufactured goods. Through this process of unequal exchange, the world system functioned as a gigantic pump, constantly transferring value and capital from the underdeveloped to the developed capitalist nations. International inequality of development now combined a growing international concentration of capital at the expense of underdeveloped nations with a growing gap between different levels of productivity of labour.

The epoch of imperialism, as opposed to that of laissez-faire capitalism, can therefore only be understood as a result of the sum total of all these laws of motion. Sharpening competition in the West led to a new technological revolution (the electric motor and the explosion motor substituted the steam engine as the basic motive force in industry), to an increased organic composition of capital and to a decline in the rate of profit, which was precipitated also by a shift in the relationship of forces between capital and labour in the West and the inability of capital to compensate for this decline by a steep rise in the rate of surplus value. From these causes resulted a decline in the number of leading firms in many branches of industry, the appearance of various forms of capitalist combinations, trusts and monopolies to halt price competition, momentous expansion of capital export to the ‘third world countries’, the search for colonial surplus profit, the increased exploitation of underdeveloped countries and the general increase of worldwide contradictions, between imperialist countries, and between these powers and incipient tendencies towards revolts against colonialism and imperialism in the ‘third world’.

The temporary defeat of world revolution outside Russia after the First World War I brought all these contradictions to their paroxysm without offering a solution. This is the basic reason for the long period of economic stagnation which characterized the capitalist world economy between 1914 and 1939.

New industrial techniques introduced during the previous period were slowly spreading throughout industry: the rise of the oil industry, the automobile industry and the electrical equipment industry became preponderant in the United States and strode ahead in Western Europe too.

But the market remained too limited to allow a high a long-term rate of growth of industrial output. The loss the Russian market; the permanent crisis of agriculture; the poverty of the colonies; the initial appearance of light industry in some ‘third world’ countries, under the spur of the war; the insufficiency of European (not to speak of Japanese) wages to allow the quick rise of a durable consumer goods industry outside the United States, these were some of the factors explaining the relatively low level of profit and capital accumulation in the 1914-1939 period (of course temporarily offset by the ‘war boom’ of 1915-1918 in the United States and Japan, and the 1923-1929 boom in most imperialist countries. We are interested here in long-term averages).

A key element in this situation was the inability of the capitalist class to radically modify any of the basic relations. It could not radically increase the rate of surplus value because resistance from the working class and postwar radicalization in the wake of the Russian revolution were too strong. It could not radically depress raw material prices further because a basic increase in labour productivity (no basic decline in exchange value) of these materials was not possible, compared to the one resulting from massive introduction of mechanized techniques in overseas agriculture and the massive growth in overseas plantation and mines during the 1880s and 1890s. It could not radically renew the productive apparatus, because the lowering of the rate of profit and of capital accumulation did not allow for a surge in ‘vertical’ industrialization, such as the one which occurred during the ‘second’ industrial revolution between, say, 1890 and 1914.

The outcome of this period of stagnation – by no means the only one! – was determined by the outcome of the protracted social struggles and international rivalries of the 1918-1939 period. The crushing defeat of the Italian, German, Japanese, Spanish and French working class made possible a radical upward shift in the rate of surplus value, and of profit and capital accumulation, which introduced economic growth of a special type, concentrated in the expansion of the armaments industry and heavy industry in general. The no less crushing defeats of German, Japanese, Italian and in a certain sense also French imperialism during the Second World War allowed the maintenance of this high rate of surplus value (in some cases, such as France, through the specific device of inflation) for a protracted postwar period, helped by the need to reconstruct materially destroyed industries and towns, and to introduce massively technological innovations already existing in the United States (and partially Britain) 10 to 15 years earlier. This high rate of surplus value and profit unleashed a dual process of ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ industrialization in these countries. Whole previously agricultural regions became industrialized. Whole branches of industry became obsolete and were replaced by new branches with a much greater fixed capital. This process was powerfully stimulated:

a) by a massive technological revolution, which brought about an average rate of increase in labour productivity unknown in the history of capitalism, except perhaps in the first decades of the first industrial revolution. It was this tremendous rise in productivity of labour that explained the possibility of both expanding real wages and inner markets, and high rates of surplus-value and of profit.

b) by massive reconstruction of the reserve army of labour through an expanding labour population, gradual absorption of the rural surplus population in Japan, Italy and France of more than 10 million refugees in Western Germany, etc., which created an ideal combination of factors for capitalism: expanding markets and rising real wages, but at the same time declining relative wages (rising rates of surplus value).

c) by a massive decline in the value of raw materials (resulting from the massive substitution of chemical for natural raw materials and from a new wave of evolution of the terms of trades detrimental to the primary product-exporting countries after 1951), which meant that growth in the organic composition of capital was not as large as one would expect given the increase in the relative value of fixed capital, and thereby also limited the fall in the rate of profit caused by the increased organic composition of capital.

In the United States, an analogous process was under way during the Second World War, although on a more modest scale, of increasing the rate of surplus value and of capital accumulation, a process which, after some delay as a result of the postwar militancy of the US working class, received its momentum in the 1950s and especially the early 1960s, produced a strong increase in the rate of surplus-value resulting from an exceptional rate of increase in productivity, with a permanent reserve army of industry (swollen by displaced farmers, an increased population and housewives turning towards gainful employment) which, in combination with a quiescent labour movement, resulted in a steady (although slow) decline in relative wages, and a significant increase in the rate of capital accumulation as compared to the 1918-1939 period. A widening market was provided not only by increased technological innovation and the permanent war economy but especially by rapid expansion of Western European and Japanese capitalism. The stimulant function of a slow increase in US commodity exports and capital exports to these sectors after 1952 on the worldwide economic boom and especially the American economy itself, has been underestimated and should be more carefully examined.

This new wave of rapid economic expansion in the imperialist countries had a dual and contradictory effect on the under-developed world. On the one hand, the sharp decline of relative prices of primary products siphoned off an increasing amount of value from the ‘third world’ towards the imperialist metropolis. On the other hand, the changed pattern of output inside the imperialist countries, with a growing emphasis on the export of fixed capital goods (equipment and vehicles), gave a stimulus to increased capital export to underdeveloped countries, especially of a public or semi-public nature, which, under the cover of ‘aid to the third world’ was in reality a permanent subsidy to the imperialist countries’ heavy industries. Nevertheless, this led to increased industrialization in ‘third world’ countries themselves.

The overall outcome of this dual and contradictory evolution of the underdeveloped economies stresses the basic pattern of imperialism. The types of industry introduced and developed in ‘third world’ countries are generally of much lower average productivity of labour than those of imperialist countries. The exchange of their products for heavy industry goods from the West continues to be unequal exchange, which siphons value away to the metropolis. Furthermore, the growing weight of imperialist monopolies in this industrialization process itself strengthens their stranglehold on these countries rather than reducing it. The combination of the internal social structure and the foreign stranglehold makes it more impossible than ever to solve the basic problems of these countries’ economies and societies, and brings about a highly explosive situation, which has led to two and a half decades of practically uninterrupted revolution in the underdeveloped countries.

IV

What specific role can be attributed to the state – or more generally to attempts at conscious intervention in the economic process – in the transformations of late capitalism since the Second World War? This is a matter of great and important controversy among Marxist economists the world over. The empirical data are clear. In all imperialist countries today, the state budget appropriates (and redistributes) a part of the national income much greater than in the past, with the possible exception of the peak years of war effort (1917 in Germany, 1944 in the United States, Germany, Britain and Japan). To this must be added state ownership of certain sectors of the economy which, in most countries, is also significantly larger than before the Second World War, not to speak of the period before the First. Both combine to create the impression that, in a whole series of key fields, strategic decisions are taken at government level which will mould the pattern of economic development to a large extent, some say to the same or even a larger extent than decisions of the great monopolies.

The controversy should not turn so much around disputes about the quantitative extent and importance of these phenomena, although some participants in the debate obviously exaggerate the autonomous nature of government decisions and forget the decisive weight of the private monopolies inside governments and central administrations, whatever may be the political coloration of the governments. One should stress in this context the increasing replacement of cash by book money, simultaneous with growing state intervention in the private sector. The key issues of the controversy are two intimately related questions: (1) What is the causal relation between the increased role of the state and the specific features of the third phase of capitalism? (2) What is the function of that role, as related to the basic characteristics of the capitalist mode of production?

On the first question, we deny that the increased role of the state is the cause of specific features of ‘late capitalism’, or ‘neo-capitalism’ (this by the way, is the reason why we prefer these labels to ‘state-monopoly capitalism’). To cite but one example, we do not believe that increased economic growth during the past 20 years in Western Europe has been caused basically by ‘economic planning or ‘flexible planning’. On the contrary, we believe that increased economic growth, which can be explained by the inner mechanism of the capitalist ‘laws of motion’, has created no need for ‘economic planning’ because of one of that growth’s specific features: accelerated technological innovation and shortened life-cycle of fixed capital, which implies the need for more precise cost and investment planning on behalf of individual monopolies, and thereby obviously stimulates coordinated cost and investment planning among those monopolies. That’s what capitalist economic programming is all about, in the last analysis.

In stating that increased state intervention in the economy is not the basic – and certainly not an autonomous – factor explaining the modus operandi of ‘late capitalism’ in no way do we underestimate important consequences of such phenomena as the high level of state expenditure (in the first place military expenditure, but not only) or permanent inflation, for example on the amplitude of cyclical fluctuations of the economy. The famous ‘new 1929’ so many economists have been scanning the sky for is simply impossible under such conditions.This does not mean that recessions could not become deeper and longer, especially if they become internationally synchronized. The basic methodological question implied in this aspect of the controversy is whether ‘state intervention’ can in the long run eliminate or even neutralize basic laws of motion of the system. This we emphatically deny. As several American and British recessions have shown, and as the West German recession of 1966-67 has strikingly confirmed, no amount of suddenly increased liquidity on the money and capital market will automatically lead to an increase of investment in those sectors already saddled with excess productive capacity at the outset of the recession, as long as these sectors are not faced with a combination of a newly expanded market and a higher rate of profit. Only if and when this coincidence occurs will private productive investment increase again. Government authorities can ‘manufacture’ recessions by tightening monetary and credit screws (which only means that they can advance the moment when the crisis of overproduction breaks out, in order to make it more moderate than it would have been if it occurred later). They cannot automatically ‘manufacture’ booms by loosening monetary and credit screws.

This leads us to the second question: What is the basic function of increased state intervention in the economy? In our opinion, this basic function is a defence and consolidation of the capitalist mode of production – in the first place of the most powerful sectors of the ruling class – against all threats which arise against it in the present world, foreign and internal. To a growing extent, this defence and consolidation of the system implies state guarantee of private monopoly profit. This is the common economic feature of armament expenditure; state financing of research and development, nationalization of loss-making sectors of the economy or those providing cheap raw materials and sources of energy to the private sector; and extensive direct subsidies and subsidies to private enterprise.

One can and should stress the socio-political function of these policies: defence of capitalism against extending revolution in the world, against the Soviet bloc, against the danger of ‘internal instability’ or even ‘internal subversion’, etc. Even the policy of high employment, albeit at the price of inflation, to which a large sector of the American and British ruling class clings as dogma, is an obvious result of an assessment of the social relationship of forces in these countries, i.e. it implies that large-scale unemployment would provoke a social. and political crisis which in the present world-context would be fatal for the system. The methods for attaining this defence of the system can vary widely. They can go from extremely sophisticated and progressive reforms – as in Sweden – to the brutal suppression of civil liberties – as in Greece – or a combination of the two, as during the first phase of the Gaullist regime in France. But the socio-political goal is always to defend the basic relations of production, the economic power and the profit of the most powerful sector of the capitalist class (even sometimes by ruthlessly sacrificing the interests of other sectors of that class). This means that at the root of the socio-political stabilizing function of ‘state intervention’ there is an economic need and an economic logic. In the famous conclusion of Hilferding’s Finance Capital, strong state intervention, ‘the open dictatorship of the capitalist class’, was foreseen as a result of the growing concentration of capital: centralization of economic power leads inevitably to centralization of political power. There is nothing wrong with this aphorism, except that it fails to stress the inner logic of the development.

Strong state intervention in the national economy is not a new phenomenon in the history of capitalism. It was a general rule at the dawn of capitalism, in the epoch of manufacturing capitalism, mercantilism and the Navigation Acts. Outside of a few privileged countries in Western Europe, state intervention played a similar role in the 19th century: to stimulate primitive accumulation of capital wherever the native capitalist class was too poor or too weak to initiate this process itself. Japan and Tsarist Russia are outstanding examples. With the emergence of imperialism, increased state intervention in the modus operandi of the system came back with a vengeance to those mother countries of laissez-faire capitalism which had progressively discarded it in the 19th century. Colonial conquest, protectionism, increased arms expenditure were general features of economic policies of all Western powers between 1880 and the First World War , be it in varying proportions and importance. Finally, the outbreak of the war, and the general introduction of a war economy in the warring states – with the exception of the United States – brought state intervention to its first historic pinnacle.

But there is a basic difference between the growing economic role of the state under ‘classic’ imperialism before 1918 or 1929 and the present-day role of that same state in imperialist countries. In the classic period of imperialism, the state had only specific tasks to fulfil, in the interests of leading sectors of the bourgeois class. The economic system was sufficiently solid to maintain itself and expand through its own autonomous functioning, be at the price of periodic crises of overproduction, sharpening of the class struggle, colonial uprisings and constantly increasing inter-imperialist contradictions which made periodic imperialist wars unavoidable.

In the epoch of ‘late’ capitalism, on the contrary, the capitalist economy is no longer capable of ensuring autonomous long-term expansion. The tasks which the bourgeois state has to fulfil blend into a new global and qualitatively different category: increasing state guarantee of private monopoly profit. In the last analysis all aspects of present-day economic policies of the state have fulfil this function. The radical increase in the rate of surplus-value, for example, which in our overall analysis is the main cause of the postwar expansion of the capitalist economy, is the result of direct interventions by the superstructure in the social infrastructure, primarily fascism, war, and various forms of curtailing free trade union activity. Centralization of political power is not simply a mechanical reflection of centralization of economic power. It corresponds to a deep inner need of the system in its period of historical decline of ‘general crisis’. Even the production of surplus-value is increasingly subordinated to tighter and stricter control over all factors of production and reproduction, in the first place labour power itself. This is the basic rationale of ‘state intervention’. It reflects the growing structural crisis of the capitalist system, which is basically a crisis of capitalist relations of production. Notwithstanding faster capital accumulation and increased economic growth in 1945-1965 as compared to the inter-war period, and notwithstanding crises of overproduction that were less deep and shorter than those of the 1914-1939 period, today this basic structural crisis of the world capitalist system is immensely deeper than in the past. The growth of ‘state intervention’ is the clearest expression of that crisis. As in the childhood of capitalism, state intervention in its period of senility means fundamentally that without the state playing a stimulating and chirurgical role, private capital accumulation cannot function on a sufficient scale to make the system function normally.

One could ask: Are we not contradicting in this answer to the second question what we maintained in our answer to the first? Isn’t ‘state intervention’ after all the basic cause of the new postwar wave of economic capitalist expansion? We think not. There is a confusion here between what, in formal logic, is called a ‘precondition’ and what a ‘cause’. ‘State intervention’ and ‘state activity’, such as crushing working class resistance through fascism, unleashing wars, organizing armament industries, introducing legislation that curtails free trade-union activity and the right to strike, all these factors were necessary preconditions for postwar economic growth. They were not its basic cause. To prove the relevancy of this distinction it is sufficient to pose the following question: Will ‘state intervention’ continue to assure such growth in the future? It should if it were its main cause. It will not, if it is only a precondition, and if the main causes are those which we quoted above, and which have probably spent themselves or are on the point of spending themselves.

V

The conclusion which we draw from the above is that the history of capitalism takes the form of a succession of long waves of over- and under-accumulation (of relatively high and relatively low average rates of growth). Each of long wave of ‘over-accumulation’ coincides with a general overhaul and renewal of capitalism’s basic industrial technology, i.e. a qualitative revolution in production technology different from the quantitative changes in technology which are a permanent feature of the capitalist mode of production. In that sense, it is evident that long cycles of ‘over-accumulation’ are synonymous with ‘industrial revolutions’, of which we recognize basically three, respectively centred around the steam engine, the electrical motor, and electronics in the last 125 years. Each of the three waves can be divided into periods of 20 to 25 years of ‘over-accumulation’ followed by periods of ‘under-accumulation’: 1849-1876: ‘over-accumulation’; 1876-1895: ‘under-accumulation’; 1895-1914: ‘over-accumulation’; 1914 -1939: ‘under-accumulation’; 1940-1965: ‘over-accumulation’. If this hypothesis is to be verified, we would have already entered, or be on the point of entering, a new long cycle with a significantly lower rate of growth, which would have started somewhere around 1966-68, signalled by the turning point of the American boom and the first important postwar recession in Western Germany. This scheme could even be projected backwards, to encompass an initial period of ‘over-accumulation’, through the rapid spread of the factory system in Britain and the western part of the continent, starting with the Napoleonic wars, or even the American and French revolutions, and continuing to the crisis of 1825, followed by a period of ‘under-accumulation’ in which there is a slowdown of economic growth which is one of the main causes of the revolutionary crisis of 1848. This ‘backward’ projection is, however, more hypothetical and calls for more caution than the subsequent scheme.

But to say that the long waves of ‘over-’ and ‘under-accumulation’ coincide with with radical changes in production technology and energy sources by no means signifies that they are caused by these changes. To proclaim such a causal link reduces ideas either to a mere tautology or to the type of circular reasoning to which Schumpeter fell victim. Scientific and technological innovations accumulate in a more or less continuous way (although it is evident that as a result of a cumulative movement, stimulated not only by basic new discoveries but also by the obligation of permanent military competition with the non-capitalist system of the Soviet-Union, the pace of that accumulation has greatly increased since the Second World War). The discontinuous innovation process, as opposed to the continuous invention-discovery process, cannot be explained by accidents, psychological reasons, or the fact that over-specialization and monopoly lead to the need for periodic renewal of firms stimulating key innovations, which introduces inevitable time-lags before revolutionary innovations are widely applied.

The basic explanation can only come, as we said before, from the sum-total of all the laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production. It is the combined operation of these laws which determines whether the additional capital to finance a supplementary ‘chunk’ of productive investment – over and above renewal of fixed capital at the ‘normal’ rate of expansion – is indeed available, and also whether the actual investment of that available capital is deemed sufficiently profitable by its owners to make large-scale innovation possible. We have already seen that the discovery of additional markets (outside or inside the capitalist nation examined, i.e. ‘external’ or ‘internal’ colonies), sudden upward shifts in the rate of surplus-value, important reductions of cost of raw materials, or constant capital in general are key factors which can explain the emergence of phases of ‘over-accumulation’, notwithstanding increased competition and increased relative impoverishment of the working class (i.e. a decline in relative wages). In the same way, limited expansion of markets, together with increasing rigidity of the rate of surplus-value and of the value of constant capital, must precipitate a sharp decline in the long-term rate of profit, which inhibits large-scale innovation processes and explains long-term periods of ‘under-accumulation’ under conditions of increasing organic composition of capital, notwithstanding sharpening competition and relatively high wages for the workers. The important point to stress is that all ‘laws of motion’ of capitalism do not operate in a linear way throughout the history of capitalism, but that their combination makes possible, and explains why, after long periods of gradual decline of the rate of profit, this rate can suddenly increase. We contend that basically this is what happened in the early 1940s and the 1950s of the 20th century. This periodic increase in the rate of profit is the basic explanation for the long cycles of ‘over-accumulation’. But, as a peculiar combination of all the ‘laws of motion’ explains why a periodic upward shift in the rate of profit might trigger a new ‘industrial revolution’, so the combination of these very same ‘laws of motion’ makes a new decline of that rate of profit unavoidable, after the forces pushing in the opposite direction have spent themselves. This is the basic explanation of why long waves of ‘expansion’ are followed by long waves of relative ‘stagnation’, like that of 1876-1895, or between the two world wars. We believe that we are entering such a long wave now.

Empirical evidence is abundant today that the average rate of profit – as calculated by bourgeois economists and statisticians (which is a far cry from a calculation of this rate on the basis of the Marxist theory of value but nevertheless provides a useful measuring stick if applied only in order to evaluate long-term fluctuations – has started to decline again. For the United States, the rate of gross profit on ‘net working capital’ declined for top boom years, from 49 per cent in 1950 to 43.6 per cent in 1955, 38.4 in 1959 and an average 45.1 per cent for the boom years of 1965, 1966 and 1967 (Federal Reserve Bulletins). For Britain, the Financial Times Annual Trend of Industrial Profits series, which calculates net profit as percentage of net industrial assets, indicates a decline from an average of 9.3 per cent in 1952-1960 to 7.8 per cent in 1961-1965 and 6.7 per cent in 1965-1968. For Western Germany, net profit as a percentage of the capital value of total industry fell from 20.9 per cent in 1951 to 18.5 per cent in 1955, 18.4 per cent in 1960 and 14.9 per cent in 1965 (all peak years of the cycle).

Simultaneously, the organic composition of capital is set to increase steeply, as the huge wave of technological innovation introduced during the previous decade spreads through the industrial system. But the resistance of the working class to further increases in the rate of surplus-value and a further decline of relative wages (the result, among other things, of increased inflation and taxation) is stiffening everywhere. The attempt to weaken that resistance through an initial increase of unemployment – consciously engineered in Britain, France and the United States, and likely to be engineered also in Italy, be it in a more selective way – has completely failed to attain its goal. On the contrary, it has increased restiveness and militancy.

The spread of the colonial revolution makes a further deterioration of the terms of trade between the ‘third world’ and the West unrealizable. And the safety-valve role played by massive exports of commodities and capital to non-capitalist countries of Europe and Asia is limited not only by the political social and military implications of this policy, but above all by the relative poverty of those countries, their inability to offer a huge mass of cheap commodities in exchange for what they would like to receive.

So in the absence of a new and disastrous defeat of the Western working class of 1933-1939 type – unlikely, at least in the near future, or a radical victory of pro-imperialist forces in crushing the colonial revolution, or the overthrow of existing property relations in non-capitalist countries, the most likely variant for the1970s is a declining rate of growth compared to the 1950s and 1960s, sharply increased inter-imperialist competition, and of exacerbation of class contradictions, on a world scale and inside imperialist countries. This will not lead to a new 1929, although a sharpening monetary crisis could have paralyzing effects on world trade and investment. But it will again sharpen the crisis of the capitalist relations of production and make the situation more explosive. All of us who are revolutionary socialists, who are not satisfied with the role merely of observers and interpreters of the historical process, but who want to transform their understanding of capitalism into a weapon for overthrowing it and liberating labour, will find ample occasions to supplement theoretical criticism with practical revolutionary activity in such a climate of deepening crisis of the capitalist relations of production.