The ability or inability to explain fascism has been a key test of all social theories and political tendencies.i Even today, important sectors of academic science and political movements say that there is no rational way in which you can explain the most extreme and radical manifestations of fascism, such as the mass murder of the Jewish people in the second world war or the way in which Hitler and his henchmen behaved towards the Soviet population in the occupied territories of the USSR after 1941. The great superiority of Marxism, and especially the legacy of our comrade Leon Trotsky, comes out in the capacity, which I think is unique, to give a satisfactory explanation of all the key characteristics of the fascist movement, the fascist parties and organisations, the fascist ideology and the fascist state.

We have to start from a negative. The original theory of the Communist International on fascism originated right after the first fascist government—that of Mussolini in Italy—took power. That initial theory came from Zinoviev, and from the left wing Communist leader in ltaly, Bordiga. It was developed to its ultimate logic by the German KPD under the influence of Stalin in the years 1929-1932. By then it had become the ultra-left policy of the so called ‘Third Period’.

This initial theory was wrong. It characterised fascism as an extreme form of anti-communist revolutionary movement. It denied that there was any basic difference between different forms of bourgeois rule. It saw in fascism essentially a terrorist rule of the bourgeoisie, of big capital directed against the radical sectors of the working class. It stressed the collaboration between the fascist and the non fascist parties and tendencies in the bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie. It tended to stress the continuity between and the collaboration between even the moderate bureaucratic leaderships of the labour movement and the fascists. It culminated in Stalin’s famous formula that ‘Social Democrats and fascists are not antipodes but twins’ii and in the concomitant formulas of creeping ‘fascistisation’, which the Maoists took up again in Europe and some Latin American countries in the 1970s and early 1980s. They used the term ‘fascism’ to describe what we more correctly call the tendencies towards a strong state. The steady increase of state repression, growing authoritarianism inside bourgeois democracy, inside parliamentary democracy, they call creeping fascistisation.

That means the progressive transformation, the actual transformation of the bourgeois state into a semi-fascist or pseudo-fascist or quasi-fascist state. That is the key mistake. Blotting out the basic differences, the qualitative differences between parliamentary bourgeois democracy and fascism.That wrong assessment has disastrous practical consequences, to which we will come back. It is not just a question of giving false definitions, of giving false labels; this wrong definition can lead to political disaster.

Trotsky led the opposition to this wrong assessment. There are some honourable exceptions who also upheld more correct positions on fascism inside the Marxist movement, essentially the Brandler-Thalheimer tendency in Germany (Thalheimer was the theoretician of the Right Opposition inside the German KPD, who went more or less in the same direction as Trotsky, although he was not as consistent).

Essentially it was Trotsky who developed a correct approach towards fascism. He understood the specific nature of fascism, its qualitative difference with bourgeois parliamentary democracy as a form of rule by the bourgeoisie. He understood what it means historically for the working class and the labour movement. Trotsky’s analysis of fascism is now the single part of his contribution to Marxism, (perhaps together with his interpretation of the Russian revolution of 1917) which is generally accepted as a genuine development of Marxist theory, not only by most of the tendencies in the labour movement, including the Eurocommunists, but also by large parts of academic theory. Generally everybody says "at least on Germany Trotsky was right". It is so obvious that it is hard to deny.

The strength of this theory is its comprehensive nature. It integrates practically all aspects of social reality into a coherent, consistent totality. It starts and ends with the key idea of the structural crisis of capitalism having reached its qualitative highest stage. This is what enables Trotsky to explain one of the greatest mysteries of fascism: its barbaric trends, its inhuman character.

Its violence reaches its strongest expression not in a backward country, not in Chile, or in Spain. Of course towards his own people Franco was a worse butcher than Hitler; Franco killed more Spaniards than Hitler killed Germans. Nevertheless the brutality, barbarism, inhumanity of fascism reaches its strongest expression in what was the most advanced civilised bourgeois country of Europe.

Germany, at the eve of Hitler’s coming to power had the biggest number of scientists, the biggest number of Nobel Prize winners, the greatest advance in theoretical science, the largest labour movement and the most progressive critical culture in art and literature. In spite of this you have in Germany this unbelievable eruption. For the eye-witnesses it was literally unbelievable. People just could not understand, they were taken completely by surprise by what was happening. One of the reasons for the tragic face of the Jews was that they could not believe it. They said "the Germans are the most civilised country of Europe, they can’t do these things. It is not possible that the fascists will do these things".

This can be explained by the fact that in Germany, for a number of historical reasons, the structural crisis had reached its most explosive form. Germany as the most advanced industrial country of Europe had lost the first World War, a lot of territory and a lot of markets for its industrial goods. It had terrible reparation costs imposed on it by the victors of the war, notably French imperialism and to a more limited extent British and US imperialism. The Versailles Treaty demanded that Germany pay these debts in gold or convertible currencies. This meant they could not solve their problem through inflation, and they had to have a permanent surplus of foreign trade.

Germany was placed to a certain extent in the same situation as Brazil, Mexico and South Korea are placed today. They had to have a permanent surplus of trade in order to bring in foreign currency. Paradoxically this turned into a boomerang on chose who imposed that upon them. Germany could only have that surplus if they cut their imports and increased their exports. This created huge tensions on the world market and an explosive struggle for exports, which would lead to the Second World War.

Of course, logically, there was no other way that this conflict could be resolved without a violent explosion.

Inside Germany this structural crisis in the economy and in industry expressed itself in a political and social form, as the crisis of traditional reformism and parliamentary democracy. These two things are based upon the capacity of granting a certain number of reforms to the working class. In exchange for reforms, the reformist leaders of the labour movement accept the reality of the capitalist mode of production and the structure of the bourgeois state. They integrate themselves into that structure, become class collaborationist, and so on.

In Germany because of the tremendous, unique strength and continuity of the labour movement, the structural crisis of bourgeois society led to a sharpening of the class struggle which put the conquest of power by the proletariat on the agenda several times. During the revolution of 1918/19 a soviet government was convened in Berlin, and the question of taking power was formally put on the agenda. In 1920, the first attempt by the extreme right wing, the Kapp Putsch, was answered by the most successful general strike in history. Everything was shut down and the military dictatorship collapsed within a few days. The trades unions raised the question of a workers’ government. In 1923, probably the most favourable moment, because the Communists had the majority or the near majority of the working class behind them, the question was posed again. Confronted with the tremendous strength of the working class, the German bourgeoisie had no way out other than to make concessions.

As a result of these concessions, many of the things we have seen spread over Europe after the second World War—forms of integrating the leaderships of the reformist working class movements into the state apparatus at municipal level, in the administration of social security, in permanent forms of consultation at factory level which are partly class collaborationist and partly the sharing of power (partial forms of incipient workers’ control) - were first experienced in Germany. Practically all the big German towns were administered by Social Democrats. All that meant money. One of the key mistakes of the ultra-left approach to parliamentary democracy of Bordiga and Stalin was that they saw reformism as a purely ideological phenomenon but they did not see the hard cash side of it.

All these concessions have to be paid for by the bourgeoisie. It means a reduction and not an increase of surplus value, an increase and not a reduction of real wages. The workers were getting something. There you have the explosive contradiction. The German bourgeoisie was internationally weakened. In order to defend itself against its international competitors it had to struggle to sharply increase the exploitation of the working class, to step up the extortion of surplus value. But the political relationship of forces which emerged from their defeat in the War, and the rise of revolution and class struggle had made this impossible. That became an insoluble, explosive contradiction. That contradiction is the root of fascism.

To understand fascism you have to understand that the capitalists have to change qualitatively the political and social relationship of forces in the country in order to do away with all these material concessions and so qualitatively increase the rate of exploitation of the working class. The changes have to be so great that they become incompatible with the existence of a living, militant labour movement capable of defending itself. The organic, structural crisis of capitalism translates itself into a crisis of bourgeois parliamentary democracy, a crisis of reformism and a crisis in the traditional forms of rule by the bourgeoisie.

Central to developments, however there is the crisis of the petty bourgeoisie. This is a very difficult question. Its analysis is also one of the great contributions of Trotsky to Marxist theory. Of all the elements of Marxist theory this is the least assimilated and understood. The historical approach to the problem of the politica; behaviour of the petty bourgeoisie is given by a classic formula of Lenin—that the petty bourgeoisie, placed between the capitalists and the working class, wavers. In the last analysis they may fall under the leadership either of the working class or of the bourgeoisie.

The wavering is accompanied by differentiation. The classic example of that is the Russian revolution. The biggest party in the country, the Social Revolutionaries, a typical petty- bourgeois party, was split between a left wing which supported the Bolsheviks and the conquest of power of the soviets, and the right wing-who first went completely over to counter- revolution under the leadership of Chernov, and then split again.

If we look at an advanced capitalist country like Germany, where the petty bourgeoisie was not only composed of peasants but of urban layers, we are faced with a problem of economic analysis. We see a tremendous turning point, perhaps one of the most abrupt in the history of the twentieth century. The German petty bourgeoisie was very prosperous during the rise of German imperialism and during the War. You could even say that with the exception of a very small layer of monopoly capitalists, the petty bourgeoisie was the layer which profited the most economically from the rise of German imperialism.

They became high state functionaries in an expanding state apparatus, middle ranking army officers, technicians, merchants and so on. They voted for the traditional bourgeois parties up until the early part of the Weimar Republic (except in the south, where they voted for the Catholic, Centre Party). This was very solid. So solid in fact that even today a dominant theory of academic sociology explains the stability of bourgeois society by the existence of large well-to-do, conservative, middle class layers.

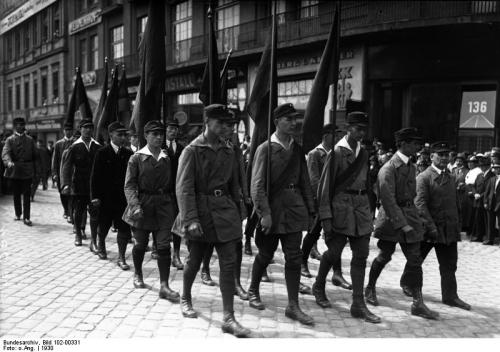

But from the end of the first World War these middle classes became impoverished. With lightning speed they lost all their savings, destroyed by runaway inflation. They had to sell their property, and jewellery and luxuries simply in order to stay alive. Many of their jobs were cut; the state apparatus was invaded by Social Democrats and—in some regions of Germany—Communists. The army was cut drastically, and thousands of officers lost their jobs. These formed some of the first members of the fascist gangs. The Freikorps was to provide the real nucleus of the SS and the SA. The Freikorps was responsible for the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and many other left wing leaders of the German labour movement in 1918/19. The material basis for the Freikorps was very clear. Thousands of army officers had been laid off and were without income from one day to the other. This went throughout the whole of German society.

This gave birth to the phenomenon which Trotsky called "the petty bourgeoisie gone mad" - gone mad not for psychological but for material reasons. You would have to have been blind not to see it. The great superiority of Marxism is that it can see and say things which are so evident. If hundreds of thousands of people lose their jobs and their livelihoods, go from prosperity to great misery, obviously they get wild. It would be unbelievable to expect them to stay the way they were before. So you have this material crisis of the petty bourgeoisie which is accompanied by a psychological and political crisis.

Trotsky also explains the psychological crisis very well in his article What is National Socialism?iii ‘They don’t understand what is happening to them’. They had always been lawful citizens; they had always obeyed authority. They had behaved as they had been educated to behave. In spite of that they were suddenly precipitated into extreme squalor and misery. So they thought that they were the victims of an extreme injustice, that the world and society were unjust—and they looked for an explanation. They developed an irrational reaction to what they considered an irrational change in their status. In other words they looked for a conspiracy. They became convinced that their situation could only be explained by a conspiracy between the reds and big capital. The third factor specific to the Nazis was that the Jews were made into the link between the reds and the bankers. But the explanation of the ‘conspiracy’ is obvious. The petty bourgeoisie was in deed caught in the middle of the explosive class struggle between capital and labour.

Marx made the point in Capital that the class struggle inside bourgeois society is an element which accelerates the centralisation of capitalism. It is easier for large firms to pay higher wages than it is for small firms. It is easier for large firms to pay social security than for small firms. So once the labour movement imposes higher wages, shorter working hours and social security (especially through legislation for everybody) small shops suffer more than big shops. So small shops disappear, go bankrupt - and blame the unions for their situation as much as they blame big capital.

A classic example is the big department store which generally sells for lower prices than small shops, so they destroy small shops. The workers’ first reaction is to be happy because lower prices raises real wages. That’s why the small shop keepers see their fate sealed by a conspiracy between the unions and the department stores. Of course in 1930s Germany many department stores were owned by Jews—and you can see the consequences. So the petty bourgeoisie is really caught between the working class and big business, not only for economic reasons but also for deeper social reasons.

The process of radicalised struggles towards revolution is a process of conquest of power by the working class. In an imperialist country this has a completely different dynamic from that in semi-colonial, semi-industrialised countries. There, the dictatorship of the proletariat has something to give to the majority of the petty bourgeoisie (land to the peasants, agrarian revolution) which represents a big step forward. This is the material basis for an alliance.

But in advanced capitalist countries the situation is not the same at all. You can not ask the victorious working class to increase the profit margins of the petty traders, or to increase the profits of the capitalist farmers, because that would be at the expense of the working class itself. There is therefore a completely different situation. I don’t say the working class can give nothing to the petty bourgeoisie, but it is not the same as in a backward country. In these circumstances the fear of the petty bourgeoisie is the fear, as Trotsky says, of falling back into the proletariat. That fear is very substantial and real. As is the fear of being destroyed by big capital.

Besides the real material basis of the conspiracy theory, there is also a historical basis. The petty bourgeoisie feels it is at the end of its real historical role—which is true. It is completely lunatic to believe that the task of the dictatorship of the proletariat in an advanced industrial country is to save the petty bourgeoisie as a social class. It is not the task of socialists to save the parasitic intermediaries. This whole complex situation explains why you have this crisis of the petty bourgeoisie. It expresses itself in desperation, and out of this desperation is born a new type of petty bourgeois movement. The change is too radical, violent and abrupt for them to accept it passively. They react against the change in a violent way. This explains the birth of a petty bourgeois mass movement of desperados who want to stop the march of history by any means—including collective suicide.

Ideologically, it is very interesting because you see a parallel of things which are happening today in countries like the US, Britain and partially France: a desperate attempt to stop the march of history by any means, including the most irrational and crazy means. This expresses itself by a tremendous upsurge of ideologies which express that irrational nature. Anti-science, anti-humanist, anti-progress, mystical, pseudo religious ideologies flower in a tremendous way. This is happening right now before our eyes in many countries and is a very, very dangerous sign. It is not fascism, but is an indication of a climate in which fascist tendencies can flower. The desperation of the petty bourgeoisie, and its organisation into a new type of mass movement is more or less unavoidable, irrespective of what the working class or its leadership does. But what is not unavoidable is the extent, scope, dimension, social impact and especially the success of this new type of mass movement.

I think it is an illusion to believe that if the working class has the correct policy, then you will have no fascists. That is an underestimation of the objective roots and depth of the objective structural crisis of bourgeois society. What you can say is that the correct attitude of the working class movement against the fascists can reduce the phenomenon, and can prevent it from becoming a real threat to the survival of the revolution. That means understanding the deadly danger of fascism for the working class. That was the real quality of Trotsky’s appeal to the German and international labour movement from 1930 on. It was a real Cassandra call, and if you read it today it is like an unbelievable prophecy. From 1930 on Trotsky said that fascism was a death machine which would kill millions of people, which would run over the workers as an armed division if we didn’t stop it in time. He understood the danger.

That is where the disastrous mistakes of the ultra-lefts and the Social Democrats come in. They completely underestimated the danger. They thought it was just more business as usual. They said fascism was already there. Well if fascism was al ready there in 1930, when nothing had basically changed, it was not such a terrible thing. People could say, well, we can live with it. It is just a little bit more of a nuisance with a little bit more repression from the state.

The qualitative change that came with the fascist conquest of power was not understood by these other tendencies. If you understood that danger, then you also understood the necessity of a broad radical reaction against it. That is where the struggle for the workers’ united front comes in. It has many dimensions to it.

First of all Trotsky insisted that psychologically and politically that the fascist movement was basically weak. This lies in the social psychology of its members. He referred to them as human dust. individually the fascists were cowards: you see that throughout history, because they represent a socially declining and weak formation. Therefore a resolute answer to them leaves them paralysed. They only feel strong if they are ten against one. They are like all bullies. If ten to one is translated to ten against one hundred, they run away. Trotsky insisted on the fact that you have to hit back at the fascists from the start. The response had to be very strong. If the fascists tear up our meetings, we go and tear up their meetings. And we do it in such a way that they do not dare come back at us a second time.

This is where the stupidity of the Social Democrats comes in. They say; ‘We are against violence, wherever it comes from’. This is pure hypocrisy: it is not even true, because the Social Democrats accept violence by the state. But it is also utterly stupid. If you oppose violent gangsters in a non-violent way, you just help them. Each time they have a success, they get carried away by it and move forward. Each time they have a defeat they retreat. You can see that through Hitler’s career and that of all fascists as a general rule. This reflects the specific character of a certain type of petty bourgeois. Strong self defence of the workers’ organisations is key to a successful struggle against fascism. Defence of meetings, demonstrations, and the working class press against fascist terrorism, hitting back at them with twice or three times as much strength each time they attack is the key, putting them on the defensive, making them lose hope and retreat.

To do that you need the united front. If each small or separate working class organisation tries to improvise self defence it will be much weaker than if they all do it together. If the working class organisations are divided from the start this makes a common defence much more difficult.

There are problems. On the one hand the defensive class collaborationist tactics of the Social Democrats, their appeal to the bourgeois state apparatus to defend them against the fascists, paralyses the reaction of the masses. On the other hand, the response of a minority of ultra-left groups can also have paralysing effects, creating the impression that small armed organisations can substitute for mass action and that you need not organise the masses. It is a blind alley to fight minority violence of the right with minority violence of the left. It misses the point—which is to organise the broad mass of the workers’ organisations in order to crush the fascists, not to deal one blow in return for another, though of course some initiatives by the vanguard can sometimes play an important role.

The question of answering fascist violence by massive counter attack is only one aspect of the tactic of the workers’ united front. Basically the problem is much deeper and much more political. The starting point we had was the deep structural crisis of capitalism, expressing itself in a big crisis of bourgeois parliamentary democracy. This is felt by the large majority of society. So large sectors of the population, large sectors of the working class and of the petty bourgeoisie are waiting for a radical solution. They are demanding a radical change.

Radical, not business as usual. Not immobility, not continuity. The opposite: a radical change. Just look at the figures of unemployment. Today we have 10-15 percent unemployment. Then we had 35-40 percent. When you have such a deep crisis of traditional capitalist society and its traditional methods of rule, the workers’ united front not only makes sense from a defensive point of view, but also from an offensive point of view. It represents an historical alternative.

The working class is much stronger in numbers than the bourgeoisie; the working class after all in an industrialised country represents the majority of the population, to which many many members of the petty bourgeoisie are tied (small shopkeepers are tied to their customers; the middle layers of the state apparatus are tied to the lower layers). There is a social web in which part of the petty bourgeoisie can move over to the workers—if the workers show an alternative to their crisis, if they pose themselves as candidates for power, pose as real challengers to the rotten order, willing to confront it.

So the transition between the purely defensive side of the united front and the offensive side, can come very quickly, as Trotsky clearly understood. His analysis has, as we will show, been completely confirmed.

The working class has tremendous potential economic power with the possibility of controlling big industry and the basic infrastructure of society. That acts as a force of attraction to large parts of the petty bourgeoisie. So when we say that the petty bourgeoisie wavers and is split, with one wing that goes towards the capitalists and one towards the workers, we must not see this is a static way, imagining that these qualities are fixed once and for all. We have to understand the word ‘waver’ in a deep historical sense: the whole class wavers, and a large part can move from the extreme right to the left according to the way it sees things to come.

Trotsky used another formula. Individually the petty bourgeoisie are cowards, human dust. But that also means they all want to jump on the bandwagon, be the victor, and when they think the left is going to win they move to the left. When they see the left paralysed or defeated, then they move to the far right. So it is important who is seen to be taking the initiative, to be seen to be winning. This plays a key role in the shifts of class forces in the period before fascist forces can take over.

The question of the working class response, working class initiative, is absolutely vital. Much of Trotsky’s analysis was just that, analysis without the depth of information we have access to today. But we now have the minutes of the meetings of the High Command of the German army, the Reichswehr, in the days immediately before and immediately after Hitler became Chancellor, January 30, 1933. It is unbelievable how much these people were completely obsessed by the question of the general strike. It is the only thing they discussed. And they had exactly the same analysis as Trotsky.

They asked what Hitler could do against a general strike of 15 million workers. The SA and the SS would be swept off the streets. They had the experience of the Kapp Putsch. They said they wanted to carry out some tests of how the working class would react: and they carried out these tests. And the decisive test for them came when the fascists made a big provocation and mobilised the SA and SS in Berlin. It was a big risk: Hitler was a real desperado.

Berlin was a red city. The Communists had 40 percent of the popular vote. The Communists and Socialists together had nearly 70 percent. Hitler mobilised the fascists to demonstrate outside the headquarters of the Communist Party, the Karl Liebknecht House. The Reichswehr in the morning said; ‘these people are crazy. They are starting a civil war. We will all be killed’. But the fascists demonstrated—and nothing happened. Nothing. The Communists mobilised to guard the house and shout at the fascists, but they were allowed to demonstrate for hours. The next day the Reichswehr said if it is like that, then Hitler can take power. There will be no reaction. The Communists will just run away and go underground. And that’s exactly what happened. If that day people had started shooting at the fascists from the Communist headquarters—and there would have been not more than a hundred deaths that day in the streets of Berlin - there would have been no conquest of power by the Nazis. The Reichswehr would have said ‘this is civil war, we don’t want civil war, it is too early, we have to weaken the Communists before we can risk it’.

But if nothing happens, then you have what has been described in a fantastic formula as a ‘one-sided civil war’, a civil war in which only one of the two camps is armed, only one camp shoots and only one camp acts, while the other is completely paralysed, demoralised, split. In that case the victory of the first camp is without doubt. But each time they meet resolute resistance, the fascists immediately retreat, because they know the score. The objective relationship of forces is tremendously in favour of the workers. And this is the other side of the story, one that can make you weep.

Contrary to the lying myth which we must categorically reject, it is absolutely untrue that the German workers, because they were ‘disciplined’, ‘reformists’ or ‘labour aristocrats’ had as their normal reaction co accept ‘law and order’ and fascism coming to power. That is absolutely untrue. The spontaneous reaction of the German workers was to resist fascism, by all possible means including violent means. Hundreds and hundreds of initiatives were taken at local level, factory level, neighbourhood level, to show that. We now have tremendous evidence of this. I have many examples, and I feel very strongly about this, because that is one of the turning points of history, where the responsibility of the Social Democratic and stalinist misleaders of the working class is so terrible. What they did at that time cost mankind 80 million deaths. It is not the fault of the workers; not the fault of our class. It’s not because of anything inherently wrong with the German labour movement. The fault is with these leaderships and exclusively with them.

After Hitler came to power, when the terror had already started and there were al ready thousands leaders of the Communist Party, trade unions, Social Democrats and members of far left organisations in concentration camps, in many German towns the largest mass demonstrations ever recorded took place, larger than during the revolution of 1918-19. In the town of Lubeck, a local moderate leader of the SDP was arrested and sent to a concentration camp. Of a town population of 400,000, 250,000 came onto the streets to demand his immediate release. That kind of movement had never been seen before—or since.

We also have the minutes of the SPD leadership in the days after Hitler became Chancellor. Every day there were delegations from all over the country coming to the headquarters of the SPD, calling for a general strike, calling for a united front with the Communist Party, saying that they still had time to do something and should not stay passive as the fascists began murdering their comrades. The response was terrible, the classical logic of reformist class collaboration. The SPD leaders argued ‘we have to save the organisation at any cost, any price, the organisation is more important than anything else. Hitler will respect its legality. We cannot risk shedding the blood of German workers.’ As a consequence 80 million died. What terrible, unbelievable blindness: not understanding the nature of fascism. Of course they didn’t even save their own organisation. The leaders of the unions also had terrible illusions; they capitulated completely to the fascists, accepting the new government, accepting national solidarity and national unity, rejecting any notion of Marxism, class struggle or socialism: but three weeks later they were banned.

The ultra-left line of the KPD, inspired by Stalin, objectively helped the fascists to liquidate the German labour movement. This ultra-left line had a double content. On the one hand, complete under-estimation of the qualitative change which the destruction of parliamentary democracy would bring for the labour movement; complete underestimation of what fascism really meant, and in that sense it went in exactly the same direction as Social Democracy. The KPD thought there would be no real change: fascism was already there. They called successive governments in Germany ‘fascist’ - Brüning was a fascist, they said, von Papen was a fascist, von Schleichen, too; so Hitler wouldn’t really make any difference. Of course that was completely stupid. It meant that the KPD was completely taken by surprise. They had not properly prepared to go underground, and threw their militants into minority struggles against the fascists. Nearly their whole leadership was arrested; they did not even prepare their own safety.

But the other side of the political line was that as a result of the identification of the strong state with fascism, they saw Social Democracy, which was still administering part of the state, controlling municipalities, municipal police, had part of the state under its control, as their main enemy. Their strategic line was that you first had to break Social Democracy before you can win against the fascists. The reality is quite the opposite, which is that it is necessary first to join with the Social Democrats to beat the fascists before you could beat the SPD. That’s what happened in the Russian Revolution, where the Bolsheviks and Kerensky beat Kornilov before the Bolsheviks beat Kerensky. Had Kornilov been victorious we would never have had the October Revolution.

This KPD approach was wrong, but also had psychological implications. A deep hostility was inspired between Communists and Social Democrats. The KPD was strong among sections of the unemployed and youth, while the majority of organised workers still backed the Social Democrats. The KPD of that time is the only example in history of an ultra-left mass party—getting 18-20 percent of the popular vote. This is really tragic. The crazy logic of the KPD split and broke up the labour movement. It ran against the profound instinct of the workers to link up together against the fascists. If the KPD had been able to identify with this instinctive response, history could have been completely different. But the KPD argued for the concept of the united front from below—seeking collaboration at local and factory level, but without any agreement at leadership level. That was unrealistic and utopian, to suppose that the workers of the SPD were ready to act against their own party—effectively going over to the Communist Party. The reality was that they remained largely loyal to their party, not least because of the line of the KPD itself. To build a united front it was necessary co make proposals to the leadership as well as the rank and file: the united front from above and below. The KPD’s refusal to fight for that destroyed the German working class movement.

So the function of fascism is to completely destroy the organised labour movement, to atomise the working class, to substitute for a collective sale of labour power the individual sale of each worker’s own labour power, returning to the situation before the rise of the trade union movement: this was the precondition for forcing a radical increase in the rate of surplus value. Under the Nazis the rate of surplus value increased by 300 percent: for the same amount of wages the bosses got three times the profit in 1938 compared with 1928. This is unheard of in the history of capitalism. At the same time unemployment declined. Just imagine what might have happened in a free labour market with free trade unions in the same period. This can only be explained by the total destruction of the labour movement by the fascists.

It is not true—as the Stalinists, Maoists and others would have us believe—that the fascists only destroy the radical wing of the labour movement, the extreme left. In fact they destroy the whole labour movement including the most moderate, most reformist elements, the Catholic unions, any form of organisation of the working class. The primary Nazi weapon was demoralisation, which, combined with terror, scattered a powerful labour movement built over a hundred years of activity and unparalleled efficiency. The betrayals of the right wing, class collaborationist Social Democrats on the one hand and the Communist Party leaders who followed Stalin’s ultra-left line on the other combined to bring about a devastating defeat.

Learning the lessons of that defeat and defending Trotsky’s theoretical strengths are vital for Marxists if we are to avoid repetition of these catastrophic errors.

First published in John Lister (ed.), Ending the Nightmare. Socialists against Racism and Fascism (London, 1995).

i This text is an abridged transcript of a speech to the Fourth International’s educational school in the IIRE Amsterdam, in 1987, and was originally titled ‘Learn the lessons of Germany’.

ii Quote from Stalin’s 1924 article Concerning the International Situation. Online at [https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1924/09/20.htm].

iii Leon Trotsky: What Is National Socialism? (June 1933), online at [https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/germany/1933/330610.htm].