Review of:

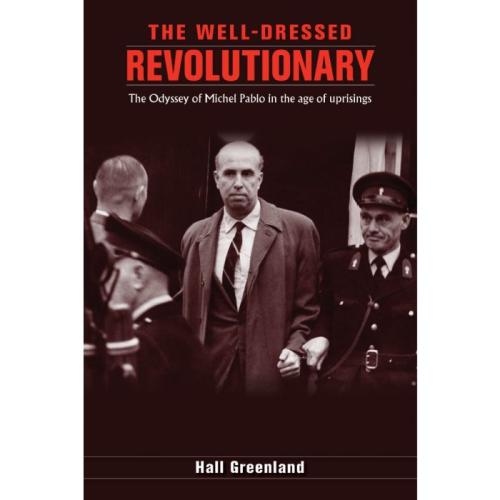

Hall Greenland: The Well-Dressed Revolutionary. The Odyssey of Michel Pablo in the age of uprisings.

Incarcerated by a Greek dictator, narrowly escaping the nazis in occupied France and tried and convicted for aiding the Algerian revolution in the Netherlands in 1961. Never a dull moment for the well-dressed revolutionary Mihalis Raptis. Hall Greenland wrote a sympathetic but critical biography of the man better known as Michel Pablo, a long time secretary of the Fourth International. Someone to admire or to debate. But to hate, to vilify? Unfortunately the name Pablo and the derived concept of Pabloism stand for something else. At least in the eyes of self-styled ‘orthodox’ Trotskyists. Even today Pabloism still seems to be revisionism incarnate for some. For those who want to know who this man really was, where he came from and what his aims were this biography sheds light on an original thinker who indeed was anything but orthodox. But what is an orthodox Marxist, except for a contradiction in terms?

Born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1911 from Greek parents, Raptis grew up in Crete and went to Athens to become a civil engineer. There he joined the left communist Archeo-Marxists and finally a Trotskyist organisation. In 1938 he came to France together with his lifelong companion Helene/Elly Diovouniotis. From the central leaders who helped bring together the European Trotskyists during the war, he and Ernest Mandel were the only two to survive. From 1943 until his arrest in 1960 Pablo, as he was to call himself during and after the war, was the secretary and most influential leader of the Fourth International. From 1961 he led his own international current, at first within the framework of the Fourth International and from 1965 outside it. In the eighties and nineties Raptis was an influential public figure on the Greek Left, writing columns in two daily newspapers.

In order to understand the real Pablo, Greenland has to explain a lot about the debates among the followers of Leon Trotsky, who had to come to grips with a reality they had not been prepared for. Already during the war, with large popular resistance movements in France and Italy with a strong presence of the Stalinist communist parties, they were uncertain about what to do, some of them taking refuge in sectarian positions. After the war Europe was divided between the two cold war blocks. Stalinism was stronger than ever, and though there were radical movements and possibilities for deeper change, the workers movement came out of the post war period divided between Stalinists and social democrats, with the revolutionaries more and more isolated.

Ways out of the desert

Michel Pablo tried to provide answers for the new realities, but obviously he was not infallible. “In his search for a way out of the ‘desert’ of isolation of the International he would be drawn to what were to prove mirages, although they were not entirely illusory.” On top of that his handling of organisational matters in the Fourth International did not help. Of course it was important to understand that whatever the future was going to bring, important developments would take place in and around the large Stalinist and reformist workers parties. And ‘orthodox’ reactions from part of the Trotskyists did not help in finding concrete orientations that went above the level of propagandist sects.

The sweeping conclusions Pablo drew from his analysis of the situation were twofold. First, there was a risk of a new world war in the near future. And second, given the relatively weak forces of the Trotskyists they had to be where the masses were, in the mass parties. This policy was contested by a majority of the French and American organisations and in 1953 led to a split that was partly overcome ten years later. The reality of 1950 was a real war in Korea. The world war was not only Pablo’s fear, many analysts at the time expected it. Or even wanted to organise it like the original commander of the American forces in Korea, general MacArthur.

The mirages Greenland mentions were elsewhere. The Trotskyist forces were too weak to have much of an impact as independent parties, but also too weak to get much done inside the mass parties. And where some results were obtained, these often led to the wish to retain them by adapting to the political culture in the parties. And in the Soviet Union and the other so-called ‘workers states’ there was no crisis at first. When it came, a reform led by Khrushchev left the power of the party and state bureaucracy intact. When workers rose against the Stalinists like in East Berlin in 1953 and in Poland and especially in Hungary in 1956, the Trotskyists saw this as the first signs of the expected political revolution. They did not see that these were partial rebellions by people who had retained both memories and organising cadres from before the war, rather than forerunners of the return to the political scene of the Soviet workers. The Soviet leadership crushed the rebellions with their tanks.

The colonial revolution

In the Global South there was more than just mirages. In 1949 the Chinese communist party took power at the head of a peasant army. It helped the Koreans drive the Americans back in 1950-51. In Vietnam the Viet Minh fought the French and defeated them at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. In Cuba the Movement of the 26th of July led by Fidel Castro chased away the dictator Batista in 1959. And closer to home for Pablo, the Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN) started a rebellion in Algeria that led to a large scale colonial war in France’s front yard. Movements for independence arose in Africa and Asia. The Colonial Revolution was the most successful movement of the second half of the twentieth century. And Pablo was determined not to let the opportunities slip.

He advocated the all-out support for the Algerian revolution. He rapidly established close contacts with several FLN leaders. The FLN was under fierce attack from the French, including assassinations by the secret services. They targeted FLN leaders and (potential) providers of arms. Pablo and the Dutchman Sal Santen were the ones most closely involved. But others, from France, Germany, Argentina and Greece were involved too. They arranged the transport of money and persons across the then still real European borders. Less known is a full scale clandestine factory that was set up in Morocco to make sub-machine guns for the FLN. Dozens from Europe and the Americas were involved. Very few of them talked about it, even years after the victory of the FLN in 1962.

In France the war led to the coming to power of Charles de Gaulle, who in 1958 established a presidential system that is still functioning today. As this took place in the framework of a right wing rebellion in the army in Algeria, the International Secretariat was moved to Amsterdam. Greenland makes a plausible case for this move as being motivated by the better opportunities to collaborate with the FLN.

Amsterdam was the place where Pablo and Santen were arrested in June 1960. A very small part of the Trotskyist network was involved in a rather special operation. Of course official papers and IDs had been forged. But as an extension of this high quality graphical art and printing, preparations were made to forge French Francs for the FLN. Before the printing could get started the printers were arrested in Germany, and so were Michel Pablo and Sal Santen. A Dutch agent-provocateur, who later made a name for himself in the right wing press, had been contacted by the organiser of the print shop. The provocateur then brought in a specialist who was working for the Dutch security service. Neither the provocateur nor the ’specialist’ were ever brought to trial.

A broad campaign for the release of Raptis and Santen was started. This turned a practical defeat into a political victory, creating broad solidarity with the FLN. Raptis and Santen were convicted to 15 months. In September 1961 Pablo and Elly first went to Morocco and then in 1962, when the FLN government came to power in Algeria, moved to Algiers. Pablo became presidential advisor to the Algerian president Ben Bella, especially for the organisation of the large scale agriculture that had been nationalised.

Leaving and rejoning the Fourth International

In the mean time differences of opinion on the relative importance of the Colonial Revolution and the work in Europe had developed. It had soured the work in the secretariat a least since the move to Amsterdam. The conflict came to a new depth with the way the group around Ernest Mandel reacted to the arrests. Forging money! I think an FLN leader summarized the attitude of revolutionaries in these matters very well when he compared it to the FLN successfully robbing a bank in the preparations for the rebellion.

In a way the first ten years after Pablo’s break with the FI in 1965 were more fruitful than before. He had the opportunity to elaborate on what previously had been only hunches and beginnings.

Some of these new elaborations had already been started during his stretch in prison. He wrote articles on the Liberation of Women, on Freud, and on Plato, and an essay ‘In Praise of Trotskyism’. Greenland sees in this essay “the seeds of his departure from the iron cage of the International and conventional Trotskyism”.

The central theme of Pablo’s writing came to be the centrality of self-management as the basis for socialist democracy. It takes a large place in his work in Algeria, and it wa clearly the main lesson he drew from the events in France in 1968, in Italy in 1969-70, and in Chile in 1970-73 when Allende was president. There we also find another central element in Pablo’s political judgement. He clearly expected much from the possible dynamics of the mass movement that organised in support of the government, as he had done in Algeria after the victory of the FLN. Not without reason. But the dynamics of the self-organisation of the masses were not sufficient. His paper ‘Self-management in the struggle for socialism’ for a congress of sociologists in Santiago in 1972 makes interesting reading as his “working hypothesis for revolution in Europe”.

Between 1965 when he had to flee Algeria after a military coup and 1974 Pablo and Elly were never in one place for long. He tried to be where the action was. And apart from that the French government only tolerated his presence without granting him a formal status. After the end of the military dictatorship in Greece in 1974 he could return there. Pablo kept on writing and organising, but in Greece more as an independent left public figure. Internationally he was more and more faced with the limitations of keeping alive a small group that was obviously not immune to the political attraction of new currents like the Greens. He did not want to dissolve his current into the Green parties, and found part of his organisation doing precisely that by 1989. He himself and his closest comrades rejoined the Fourth International in 1992. He died participating fully in Greek political life in 1996. Much of the work from his last fifteen years is only available in Greek.

Greenland’s Pablo is a charming devoted revolutionary who systematically overestimated possibilities. He was generous as a person and in his respect for the opinions of others. However that respect came with limitations. It did not apply to those who resisted his entryism in the fifties nor for those who opposed his exclusive wager on the Colonial Revolution.

Almost all his adult life was shared with Helene (Elly), a strong and independent woman from an aristocratic family who accompanied him everywhere. But as that included all political meetings and she was not a person to be silent it could lead to complications. Most of his opponents and even of his closest collaborators were unhappy with it. Pablo was too much aware of the importance of her as a partner in everything to be bothered by such objections. And there were others who retained his lifelong friendship, such as Ben Bella. That friendship ended when the war in Bosnia put them on different sides, Ben Bella supporting the Muslim Bosniaks and Pablo condoning the ethnic cleansing by the Serbs. A black spot on his memory to be sure.

Greenland clearly sympathises with his subject, but shows Pablo's limitations as well. With this book, Greenland has succeeded in giving a full, balanced picture of the life and work of Michel Pablo.

Buy the book here.