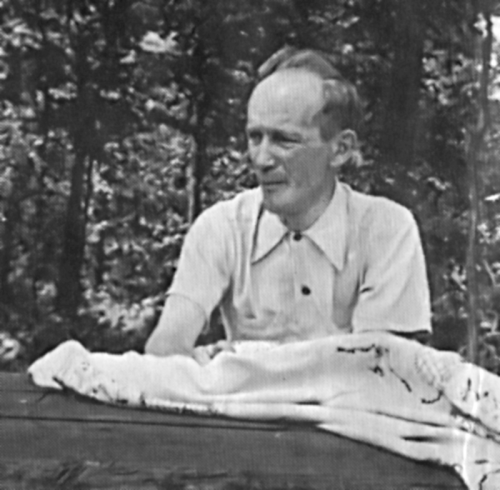

With Roman Rosdolsky, who passed away in 1967 in Detroit in the United States, the last surviving founding member of the communist movement in western Ukraine and one of the most remarkable Marxists of recent decades passed away.

The fate of Rosdolsky is characteristic of an entire generation of European revolutionaries. His peculiarity was that he survived the successive persecutions by local fascism as well as Nazism and Stalinism.

Rosdolsky was born in 1898 in Lvov (Lemberg, [Lviv]). Then part of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, this Ukrainian city was annexed in 1918 by Poland; in September 1939 it was conquered by the Soviet army; in 1941 it was occupied by the Nazis; in 1944 it was liberated by the Soviet army, and since then it has been part of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic.1

Rosdolsky’s father was a well-known Ukrainian philologist who passed on to his son a national consciousness, characterized by a feeling of national oppression. While still in middle school, Rosdolsky became a socialist and internationalist. In 1915 he was drafted into the imperial army. He took part in founding a clandestine socialist organisation that fought against the imperialist war and was in solidarity with Austrian socialists like Adler who resisted social-patriotism. Rosdolsky edited a small newspaper and immediately gave his enthusiastic support to the October revolution.

Rosdolsky was a member of the international communist movement from the start and one of the first organizers of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine. During the infamous purges of the 1930s, the entire central committee of this party was murdered by Stalin. In 1925, he refused to vote in support of a condemnation of Trotsky and the Left Opposition as he did not have the information necessary to form a judgment. He was not yet a Trotskyist but rather sympathized with the current of Bukharin. At the end of the 1920s he was expelled from the Communist Party.

In the meantime, he had moved to Vienna and become a correspondent of the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow. Under the leadership of David Riazanov, the Institute was tasked with preparing the scientific edition of the collected work of Marx and Engels (the MEGA). Rosdolsky had the task of searching Austrian archives for documents concerning Marx, Engels and the beginnings of the socialist movement. While in Vienna he became convinced by Trotsky’s criticism of Stalinist policies in the Soviet Union and the catastrophic trajectory of the Third International that was to lead to Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. The repression of the Austrian workers movement by Dolfuss in February 1934 forced Rosdolsky to leave Vienna and return to Lvov. There, he joined the Trotskyist movement and became one of the editors of a Trotskyist journal published in Ukrainian that was distributed mainly among oil workers in Eastern Galicia.

The outbreak of the Second World War forced him into long and tragic wandering, during which he was imprisoned in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and Oranienburg.

After the war, Rosdolsky ended up in the United States. Although he had a doctorate and on the eve of war had been a professor at the University of Lvov, the Cold War climate meant that the doors of American universities were closed to him. He mainly worked as a publicist and received a few grants for his scientific studies.

Education and personal interest made Rosdolsky primarily a Marxist historian. He combined thorough knowledge of Marxist methodology – as applied by the masters of Marxist history writing, Marx himself, Franz Mehring and Trotsky – with mastery of academic techniques. This enabled him to write a number of books that increasingly came to be seen as classics in their field.

During the 1930s he wrote a study of village communities in Galicia and a two-volume history of serfdom in the same region. That second was not published until 1959, in Poland. During the 1940s, Rosdolsky wrote a thorough study of the mistaken ideas of Engels and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung concerning the small Slavic peoples during the 1848 revolution. This book was not published until 1964. In the 1950s, he wrote a book on the major fiscal and agrarian reforms of the Austrian emperor Josef II, published in 1961 by the Academy of Sciences of Warsaw. During his final years, Rosdolsky collected material for a book of major historical importance, concerning the reaction of Austrian workers to the appeals launched by Trotsky during the peace-negotiations of Brest-Litovsk (appeals to world revolution) and the reasons why the revolution did not break out in Austria and Germany in January and February 1918.

The book Engels and the ‘Non-historic’ Peoples: The National Question in the Revolution of 1848 is certainly his most brilliant. In it Rosdolsky applied the Marxist method of analysis to the work of Marx and Engels themselves. Rosdolsky showed convincingly that the two founders of scientific socialism made a mistake when they made an incomplete analysis of the social forces active in the revolution of 1848. This error led them to negative judgements of nationalities such as the Czechs, the Croats, the Ukrainians and the Slovaks, nationalities that were labelled en bloc as ‘counter revolutionaries’.

Rosdolsky shows that he political division between, on the one hand, ‘revolutionary’ Poles and Hungarians and, on the other, the ‘counter-revolutionary’ Croats, Czechs, Slovaks or Ukrainians in regions such as Galicia corresponded to a class division between aristocratic landlords and peasants.

Those peasants were not destined to end up in the counter-revolutionary camp. On the contrary, they had sent their revolutionary representatives to the constitutional assembly in Vienna and they were ready to join the camp of the revolution, on condition that their most important demand, ‘the soil to the peasants’, would be granted. But the ‘revolutionary’ aristocracy stubbornly refused this demand. In the end, the peasants were driven in despair into the arms of the emperor. This book should be translated into many languages as an example of honest and thoroughgoing Marxist history writing.

Although Rosdolsky was educated as an historian, during the final two decades of his life he was interested in political economy. When, after the Second World War, he arrived as a migrant in New York, by coincidence he came across one of three or four copies of Marx’s Grundrisse that had reached the West. This monumental ‘preliminary draft’ of Capital was at that time still unknown to Marx experts. Till the end of his life, Rosdolsky was to be fascinated by the Grundrisse. As he would write, it provided him with a look into the laboratory in which Marx prepared discoveries that would shake the world.

Rosdolsky considered it an essential task to analyse the Grundrisse and popularize its most important themes. He wrote many articles on the topic in journals such as Kyklos (Switzerland), Arbeit and Wirtschaft (the journal of the Austrian trade unions), Science and Society (United States), etc. Writing these articles was a preparation for his magnum opus Zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Marxschen Kapitals, published in English as The Making of Marx's Capital. This was the second analysis of the Grundrisse to appear (the first was by a Japanese academic).

But Rosdolsky’s book is more than just an analysis. It is also a detailed search into the development of Marx’s thinking in the 1850s and simultaneously a coherent and effective defence of fundamental elements of the Marxist economic theory against attempts to revise it, attempts in both the workers movement and in academic circles. Modestly, Rosdolsky calls himself a ‘philologist of Marx’, meaning a researcher specialized in determining what Marx wanted and did not want to say in specific parts of his writings. But Rosdolsky did himself no justice with this self-description. Few Marxists delved so thoroughly into Marx’s thinking. Rosdolsky’s commentary on the Grundrisse is not limited to a few philological clarifications but sheds real light on the general method of Marx and the general thrust of his theory.

After emigrating to the United States, Rosdolsky, was no longer politically active but he still considered himself a sympathizer of the international Trotskyist movement. Although he became a close friend of Isaac Deutscher, he did not share his hopes for a gradual transition of the bureaucratic dictatorship of the Soviet Union to a socialist democracy. Rosdolsky’s differences of opinion with the Fourth International mainly concerned how to view developments such as the war in Korea and the Hungarian revolution of 1956.

But in the final years of life, the differences of opinion mainly concerned the correct definition of states in which capitalism had been overthrown but where the working class did not exercise power directly. Rosdolsky was of the opinion that Trotsky’s formula of ‘degenerated workers states’, developed 35 years earlier, no longer corresponded with reality. According to Rosdolsky it could no longer be ruled out that the bureaucracy would develop into a class if the socialist revolution in the developed imperialist countries did not come about. At times, Rosdolsky used the term ‘state socialism’, although with many qualifications and much restraint.

Although his need to complete his scientific work overtook his interest in daily politics, Rosdolsky rejoiced in seeing two developments that confirmed his trust in the final victory of the ideas of Lenin and Trotsky, ideas for which he fought for half a century: the rebirth of a left-wing communist opposition in Poland, around the ‘open letter’ of Modzelevsky and Kuron, and the mass character of student resistance in the United States against the war in Vietnam. His reaction to these developments confirms that Rosdolsky died as he lived, a revolutionary in the classic school of internationalist Marxism.

Posthumously, Rosdolsky received a final gratification. The national oppression suffered by the Ukrainian nationality under the Stalinist regime is now implicitly recognized by several official communist parties, most of all the Canadian one, a party with many members of Ukrainian descent. In the Soviet Ukraine itself, a struggle has erupted over the re-introduction of the Ukrainian language as the official language of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Ukraine, despite all the open and covert attempts at Russification. In this regard as well, Roman Rosdolsky did not struggle in vain.

1 Ukraine became independent in 1991.

Originally published in Quatrième Internationale, 33, April 1968, pp. 70-72. Translation by Alex de Jong.